Are You Good At Using AI?

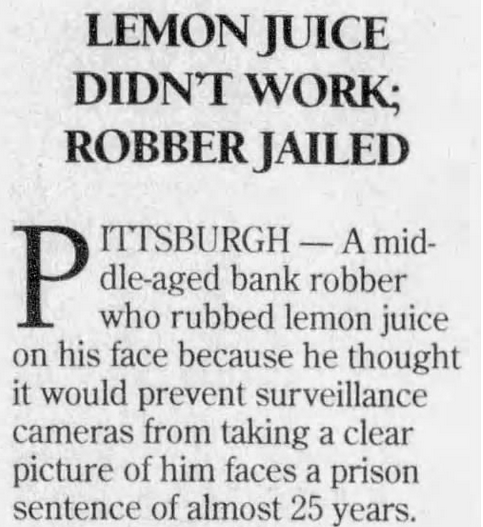

That’s the actual headline describing a bizarre level of self-assuredness: a 46-year-old bank robber who believed that rubbing lemon juice on his face would prevent security cameras at two Pittsburgh-area banks from recording him. The technology wasn’t new; as this was 1995, a full 30 years after security cameras had been in use at most banks. What explains the audacity of this bank robber? Self-confidence, according to the prosecutor in the case. As he was being taken away in handcuffs, the bank robber apparently muttered, “but I wore the juice.” (Kruger and Dunning, 2009)

It’s a stark illustration of an all-too-human phenomenon: often, the people who are terrible at something fail to realize they are terrible at the thing. The bank-robbing incident inspired a Cornell psychology professor and his graduate student to publish a paper on the now-fairly-well-known Dunning-Kruger effect:

“...when people are incompetent in the strategies they adopt to achieve success and satisfaction, they suffer a dual burden: Not only do they reach erroneous conclusions and make unfortunate choices, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to realize it. Instead, like Mr. Wheeler, they are left with the mistaken impression that they are doing just fine.” (Kruger and Dunning, 2009, bolding mine, as I want to point out that either Kruger or Dunning was apparently a fan of puns).

It’s easy to laugh at the bank robber, but we’re all subject to self-delusion. Not to accuse you, dear reader, of such a thing, but let me ask:

Do you think your teaching is above average?

If you do, you’re not alone. According to a survey of Nebraska professors in the 1970s, 94% thought their teaching was above average, and 68% thought their teaching was in the top quartile (Cross 1977). The author attributes this to “smug self-satisfaction” among professors broadly, but the phenomenon isn’t unique to teaching. Consider:

- Driving - 88-93% of American drivers think they’re more skillful and safer than the average driver (Svenson 1981).

- Research - a study in Nature showed that 99% of researchers rated themselves as following good research practices as much as or more than other researchers (with researchers in the medical and health fields being MOST likely to overestimate their own abilities) (Lindkvist, Koppel and Tinghog 2024).

- Personality Traits - 87% of Stanford undergrads rated themselves as above average on positive personality traits such as dependability and objectivity and below average for negative personality traits such as snobbery and selfishness (Pronin, Lin and Ross 2002).

- Poetically, AI also overrates its own abilities in at least one domain: judging how well it performed on mathematical proofs for the USA Mathematical Olympiad. While only one model scored higher than 5 out of 100, large language models rated the results up to 20x better than humans did (Petrov et al 2025).

What do teaching, driving, research skills and measuring personality traits all have in common? Roughly, a) there’s no objective measure of success, b) we are the (imperfect) auditors of that success, and c) the mistakes (unless they’re huge) are easy to miss. As a result, we overestimate our own abilities.

You get the point: knowing where you stand - particularly when there aren’t concrete measures of performance - is hard. All these same characteristics apply to using AI, making it tough to know whether you’re any good at it.

Why You Should Improve Your AI Skills

Not to state the obvious, but using AI well matters for future performance in most jobs.

A relatively ancient (2023) study of consultants found a 40% increase in the quality of their performance on a variety of tasks (Mollick et al 2023). And that was using a model not nearly as powerful or integrated as today’s AI tools.

Further, while it’s easy to be distracted by students who use AI to take shortcuts (i.e. cheat), the overall impact of AI is positive. A meta-analysis in Nature showed that ChatGPT has a “large positive impact on improving learning performance (g = 0.867) and a moderately positive impact on enhancing learning perception (g = 0.456) and fostering higher-order thinking (g = 0.457)” (Wang and Fan 2025).

A Caveat: Don't Confuse Frequency With Fluency

Using AI often is not the same as using it well. I love the term “AI Idiot” to describe someone who treats AI as an all-knowing oracle, uncritically accepting its results. They’re people who might use AI to make them sound fancy in an email or to insert an - unnecessary? - em... dash into their writing (oh, AI’s proclivity for those dashes…)

While it’s important to use AI enough to find its idiosyncrasies, achieving AI fluency is about knowing how to use AI well. Often in the classroom, AI is the wrong tool for the job. Becoming fluent in AI is like becoming a judo master, learning to harness the power and only using it with restraint.

A Universal Framework of AI Literacy

It’s a tough question to answer because asking “Are you good at using AI?” is really asking something deeper:

Are you good at thinking and processing information in collaboration with a machine?

That’s the biggest shift that AI brings: instead of using computers to do routine, predictable tasks (word processing, etc.), we now can use the machines to brainstorm, solve problems, and provide feedback. It’s intelligence on tap. And working well with it combines skill, mindset, ethics, and critical thinking in new ways.

Several organizations have attempted frameworks for understanding the intricacies of AI literacy, but my favorite comes from the Digital Education Council:

But how does this chart apply to the multi-faceted roles of a healthcare professor?

We’ve adapted the chart to five “domains” in which to use AI. The goal: wherever you are in your AI adoption, look to see an example of what you might try next.

At Level 1 in a given domain? See whether something from levels 2 or 3 might be the right level of challenge for you.

How to use this chart:

- Self-assess. Choose the box where you most often fall in each domain.

- See where you can up your game. Find the box that looks most appealing to you, and find a way to move toward the level of fluency you seek.

- Pick one example from the chart and implement it this semester.

Free Faculty Training Around AI

Want a more comprehensive overview of how to use AI in the classroom? ReelDx offers free faculty trainings for our partners. We’ve traveled the country the past three years talking to PA educators, NP educators, DO educators, and EMS educators about how to use AI in the classroom. Currently, we’re slated to run a “Lunch and Learn” for two prominent NP programs (who are going in on the lunch and learns together).

If you’re interested in scheduling one for your faculty, book a meeting with me here.