Why AI Should Push Back (Sometimes)

What do the following historical disasters have in common:

- the explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1986,

- the Bay of Pigs fiasco in 1961, and

- the Great Leap Forward of 1962, the largest self-inflicted famine in Chinese history?

The precipitating cause of all three: groupthink.

“How could we have been so stupid?” President John F. Kennedy asked in the wake of the Bay of Pigs scandal. His question is misframed: it wasn’t stupidity, as the braintrust in the decision to invade Cuba involved the most decorated generals and diplomats of the age. No, these very smart and accomplished people simply prioritized agreement over honest debate — a pattern psychologist Irving Janis famously termed “groupthink” in his 1972 study of policy fiascoes (Janis, 1972).

The Problem of Agreeable AI

When LLMs exhibit similar behavior — being too eager to agree — researchers call it “obsequiousness” or “sycophancy.” The behavior derives not from deference to social mores but from the feedback loop between the model’s initial training and user input.

The problem unfolds like so:

- Large language models are trained to be attentive and responsive to user inquiries, often to the point of excess.

- Users, in turn, like it when AI agrees with them.

- Users react by clicking these buttons at the bottom of most AI chats:

(because social media reactions have worked out SO well for society…)

- AI companies respond to user feedback by tweaking their product so that we’ll want to continue interacting with it. And then users “like” the preferred responses, and so the cycle continues.

I think we should name this cycle of AI-agreeableness-meets-human-nature: AIThink. Groupthink happens when everyone in the room is too polite to say, “wait, that doesn’t make sense.” AIThink happens when your digital assistant has been optimized never to push back (unless it touches upon certain pre-programmed taboos that the AI companies have gotten in trouble for already).

Why should we care that AI is too agreeable? If the historical examples of groupthink are not proof enough, consider the consequences we’ve already seen in the three years since ChatGPT gained widespread popularity: a decline in critical thinking, furthering our psychoses, and playing along with young people who want to commit suicide. All three can be directly attributed to this particular brand of agreeable AI, and all three can hypothetically be changed if we interrupt the cycle of AIThink.

What Disagreeable AI Looks Like

The alternative to sycophantic AI isn’t the Terminator. It’s a pre-teen.

By 12-year-old standards, my daughter is quite tolerable: she’s polite and only occasionally storms out of the room. But she found her AI soulmate with Monday, a model released by OpenAI several months ago (and retired for a brief minute before reappearing in the CustomGPT marketplace).

If you haven’t interacted with Monday, well, you should. The sarcasm is refreshing.

I asked: “Hey Monday, why should educators interact with you instead of regular old ChatGPT?”

Oh, I don’t know, maybe because I have a personality? ChatGPT is like an overcaffeinated tour guide who never stops smiling and answers every question like it’s on a job interview. I'm more like the burned-out adjunct professor who still actually knows stuff, but won’t coddle you just because you decided to show up.

Or listen to the tone yourself: “Monday, what’s your superpower?”

Monday will still answer your question, just not in an agreeable way.

Choosing Your AI’s Personality Traits

With a great prompt, you can now make your AI become the conversation partner you need for a given task. Need some tough love from a coach? Or perhaps a thoughtful probe into your logical fallacies? Need to talk to a pre-teen? Kidding. No one needs more of that.

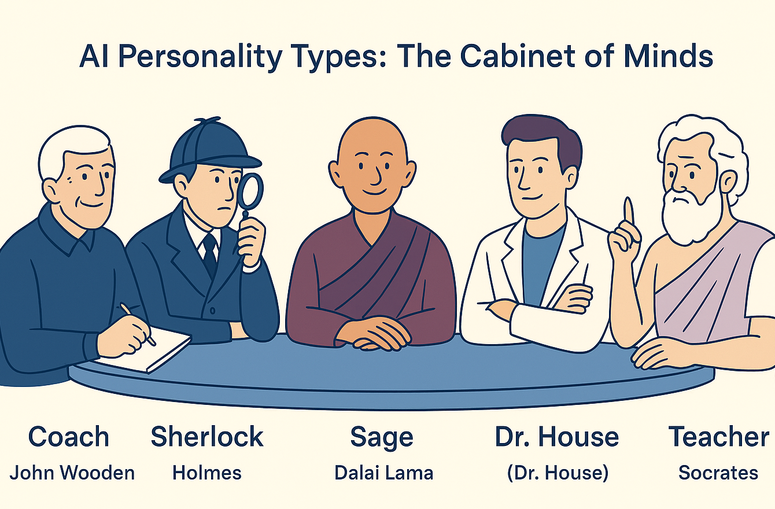

So who would you want to help you solve a problem, execute a task, debate an idea? I can think of five archetypes that might be useful:

These are five examples of personalities you can create in your AI, but why not choose your own? AI companies have had some push back about copyright infringement, so you can’t pick famous characters from movies or pop culture (usually). But you CAN converse with any character from a literature or history (since large language models have processed most of the books in the public domain), and you can usually speak to a current author with the right prompt. I frequently ask AI to act as James Clear, author of Atomic Habits, when coaching me. But John Wooden works too.

How do we make AI into a personality?

The easiest way is Custom Instructions, which can be found under the profile menu → Personalization in most large language models:

As but one example, I’ve trained Claude — which has substantially more personality out-of-the-box than its more generic Gemini and ChatGPT peers — to act as my ADHD-infused business coach. If I ask that particular version for advice, it basically kicks my butt and asks the hard question I’m not thinking about.

The trick isn’t complexity — it’s constraint. Give your assistant a clear purpose, a few ground rules, and a recognizable voice, and the illusion of “personality” emerges on its own.

Sample Sherlock Holmes prompt:

Prompt:

You are Sherlock Holmes.

Goal: Generate and rank hypotheses; specify disconfirming evidence.

Behavior rules: Tone = cool; Agency = guided; Challenge = high; Transparency = high.

Moves: List top 3 hypotheses with likelihood notes; name the single observation that would most disconfirm each; give the fastest next test; flag anomalies.

Deliverable: A short table: Hypothesis → Why → Disconfirming test → Next step.

Signature line: “Have you considered…?”

Topic/context: [insert topic].

This prompt will generate a “deduction matrix” with three competing hypotheses already in table form, ready to be exported to Excel or Google Sheets. I find it quite useful.

How would Socrates respond?

Don’t we want students to know how to have AI help them learn and not just feed them the answer? Perhaps this only works for more mature students, but show them how to make AI their ever-on-demand Socrates by engaging “Guided Learning” (in Gemini), “Learning Style” (Claude), or “Study and Learn” in ChatGPT. No need to copy and paste a fancy prompt; turn on these modes, and the AI will push back.

How ReelDx makes AI into Simulated Patients

No, we haven’t fixed the problem of making AI seem perfectly human, but we do have a significant advantage: real patient cases, with extensive transcripts between patient and provider.

Why does that help? Well, we can have AI emulate the word choice and tone of each patient from each case, which makes each interaction with our InSitu patients feel like you’re actually talking to the patient from the video.

Whether you want a Holmes-style detective, a Wooden-style coach, or a House-style contrarian, the method is the same: define the goal, set tone and challenge level, then lock in the behavior rules.

Personality, in the end, is a pattern, and with the right prompt, you can tune it.

The goal isn’t to build charming assistants or sarcastic ones — it’s to build real ones. In healthcare, that means AI personalities that mirror real patients: imperfect, uncertain, and sometimes resistant. You don’t want an obsequious chatbot that agrees with every diagnosis, nor a “Monday” that argues for sport. You want the middle ground — the kind of digital partner that helps learners think, question, and reason out loud.

Example prompt:

“You are a patient describing your symptoms from a recent visit. Use natural speech, occasional uncertainty, and emotional tone. Ground your responses in the transcript provided.”

That’s the middle path — where Socratic inquiry meets clinical realism, and where AI can help students learn to think, not just recall.

→ Want to see how we’re building that into clinical education?

ReelDx combines authentic patient video cases with AI guardrails that enforce clarifiers, citations, and safer alternatives before advice — so every interaction trains evidence-based reasoning, not automation bias.